We learned some wrong lessons from the rise of Nazis - part 2

On a previous post, I discussed how we learned a wrong lesson about parliamentarism and presidentialism from the rise of the Nazis. It was the presidential aspects of Weimar Germany - the emergency powers conferred to the president, the power to name the chancellor, the power to dissolve parliament - which fueled the breakdown of democracy, not the parliamentary aspects. It is not worth repeating all the arguments, so do read the whole thing.

The other main wrong lesson we supposedly learned from the rise of the Nazis is that it is an example of the dangers of majority rule. The fist point to argue against this hypothesis bears repeating until it becomes common sense: Hitler never had a majority in parliament. He was appointed by the president on the recommendation of Pappen. A true parliamentary system depends on such majority for any person to accede to the office. Counterfactual exercises are always hard to conduct, but nothing indicates that Hitler would have an easy time being appointed by the majority of parliamentarians who were not members of the Nazi party. In fact, the German parliament was having difficulty forming any kind of majority: "the [communist] KPD, following orders from Moscow, rejected overtures from the Social Democrats to form a political alliance against the NSDAP."

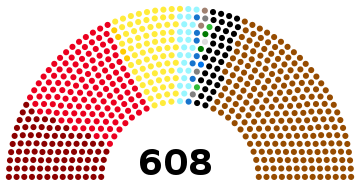

This may sound like a neglectable aspect of a democracy which was already in advanced process of decline, but the difficulty for the majority to rule was a constant aspect of the whole existence of the Weimar republic. Much of the influence of Carl Schmitt, the main jurist who provided the legal theories for the rise of nazism, derives from the frustration with an incapacity for the majority in the German parliament to rule: "governments frequently lasted only a year, comparable to the political situation in France during the 1930s. The major weakness in constitutional terms was the inherent instability of the coalitions, which often fell prior to elections." A good share of this incapacity relates to the lack of assurance that any coalition could have assurances it would lead the country, given the presidential prerogatives.

Well, if Weimar Germany does not illustrate the risk of majority rule, then could it be argued that Nazi Germany itself does illustrate that risk? Surely not. After the Enabling Act, Hitler became a dictator, decisions did not derive from any majority, they derived from him.

On the definition of majority rule

If you are inclined to object that even if Hitler did not have to formally make his decisions based on majority rule, his power still derived from the support of the majority of the German masses who legitimized it, then you are reading the situation through a Schmittian lenz. The idea that popular support, expressed through acclamation directly from the masses, and with no intermediate representation such as parliaments, can be perceived as the true expression of popular will can be traced back to Carl Schmitt. Yet it is wrong, not only in a moral sense, but in a descriptive sense.

As I argue in the book, this type of popular manifestation is not representative at all of true popular will. A first condition for popular acclamation to represent the popular will is that it has to be consistent. Given the same preferences and the same people, it should elicit the same results if the relevant options are the same. Yet this is not the case. Even if popular acclamation relied on proper voting, it would be subject to potential cycling, as shown by Arrow's theorem. Majorities negotiated with reasonably low transaction costs, however, do elicit a consistent result, which happens to be the utilitarian optimum, as shown by Parisi.

But even if you are skeptical of the applicability of Arrow's theorem objections, there are other reasons which should make us skeptical that acclamation represents any sort of majority preference. The first is the expressive voting theory. People's incentives to express their opinions are very different than people's interests. Inside an assembly, the incentives are more aligned. Second, and relatedly, popular acclamation suffers from the risk of herd behavior, which can be perfectly rational from an individual point of view but lead to inneficient outcomes.

Majority rule, properly understood, is a well-established mechanism to be used in the context of parliamentay procedure, which governs how assemblies make decisions. The principle is that, after debate has happened in an orderly manner, minorities have been given wide opportunity to speak, then a majority decides. The "majority" decides on each specific issue, and there may be as many majorities as there are questions. Often groups will vote together, particularly if they are organized as parties, but even then majorities shift and parties have to pay attention not to completely isolate any group lest they lose their capacity to ever win on any issue.

Majority rule cannot guarantee that a group will not be opressed by another. We need to ensure this through auxiliary methods such as making politics more multi-dimensional. But it is better than any other system, including for such protection.