The risks of direct democracy

In the book, I try to make a probabilistic estimation of how likely it is that parliamentarism really is much better than presidentialism. I try to gather the best information from various areas and combine it to make the best estimate possible. So I consider the current differences in indicators in parliamentary vs presidential countries, the historical evidence, informal theory, formal theory, statistical evidence, auxiliary evidence from local governments and companies. I also consider that most authors, both critical and in favor of parliamentarism, consider presidentialism to be more "plebiscitary", so the evidence for direct democracy should also count. And in the book, I say that, although I am not convinced, the academic literature gives some support in favor of direct democracy, so that attenuates the reasons in favor of parliamentarism (but not by much). In this post, I will explain why I am not convinced that direct democracy is that beneficial.

As Achen and Bartels argue, a lot of the defenses of direct democracy are tautological. There are surveys of what people would choose if they were to decide. They compare the results of these surveys with what the results of direct democracy are and find that they match. As Achen and Bartels put it: "Any policy adopted by referendum or initiative must, by definition, be preferred by a majority of voters - and probably, barring substantial biases in turnout, by a majority of citizens - to the status quo." If you are skeptical of the capacity of referendums and initiatives to elicit good decisions, you will hardly be convinced by surveys showing that people say they would prefer the eventual results that initiatives do deliver.

In the book, however, I argue that we should not take opinions expressed by voters or survey respondents at face value. First, there are the problems associated with Arrow's paradox and the possibility of agenda manipulation which derives from there. As Hayden puts it: "intransitive social orders permit manipulation of social choice through agenda control. Since any alternative in an intransitive social order can prevail if put to a vote at the appropriate moment, control of the voting agenda becomes 'tantamount to dictatorial power.' For these reasons, the condition of transitivity is essential to ensuring that social choice functions produce meaningful outcomes." As I argue in the book, parliaments can avoid the negative consequences of Arrow's paradox by providing an environment of mutually beneficial exchanges which may be reasonably be expected to be followed through.

Second, the theory that voters are both informed enough that they can reach better decisions than their representatives and not informed enough that they cannot control representative's actions is contradictory. If people are perfectly capable of monitoring the whole policymaking process as direct democracy presupposes they can, then they have to be able to monitor their representatives. Representatives should be no more than puppets to the voters-puppeteers. That voters are not puppet masters seems uncontroversial for elected representatives is evidence against direct democracy. To see that controlling representatives is not that hard if voters have enough information, think of the Electoral College in the United States. When the system was first envisioned, electors were supposed cast their presidential vote according to their conscience. But it was all too easy to 1) ask the electors to vote for the presidential candidate of preference and 2) verify if they had followed through with their promise. This connection became so automatic in time that nowadays we do not see any role for the electors whatsoever.

Third, there is the problem of rational irrationality and expressive voting (which, in the context of surveys, is very related to social desirability bias). In order to avoid repeating the arguments in the book, we may use the fact that surveys and votes do correspond well enough and expand our evidence on rational irrationality beyond what I have already discussed and talk about the challenges of contingent valuation.

According to Wikipedia, "Contingent valuation is a survey-based economic technique for the valuation of non-market resources, such as environmental preservation or the impact of contamination. While these resources do give people utility, certain aspects of them do not have a market price as they are not directly sold – for example, people receive benefit from a beautiful view of a mountain, but it would be tough to value using price-based models. Contingent valuation surveys are one technique which is used to measure these aspects. Contingent valuation is often referred to as a 'stated preference' model, in contrast to a price-based revealed preference model. Both models are utility-based. Typically the survey asks how much money people would be willing to pay (or willing to accept) to maintain the existence of (or be compensated for the loss of) an environmental feature, such as biodiversity."

The idea behind contingent valuation is parallel to direct democracy: how should we evaluate how much people value something for which there is no market price? Let's just ask them! But researchers in cost-benefit analyses have known for a long time that contingent valuation is at best a tool which must be used very wisely and at worst hopeless . Why does Hausman argue it is hopeless? Here's the abstract of his paper on the Journal of Economic Perspectives:

Approximately 20 years ago, Peter Diamond and I wrote an article for this journal analyzing contingent valuation methods. At that time Peter's view was that contingent valuation was hopeless, while I was dubious but somewhat more optimistic. But 20 years later, after millions of dollars of largely government-funded research, I have concluded that Peter's earlier position was correct and that contingent valuation is hopeless. In this paper, I selectively review the contingent valuation literature, focusing on empirical results. I find that three long-standing problems continue to exist: 1) hypothetical response bias that leads contingent valuation to overstatements of value; 2) large differences between willingness to pay and willingness to accept; and 3) the embedding problem which encompasses scope problems. The problems of embedding and scope are likely to be the most intractable. Indeed, I believe that respondents to contingent valuation surveys are often not responding out of stable or well-defined preferences, but are essentially inventing their answers on the fly, in a way which makes the resulting data useless for serious analysis. Finally, I offer a case study of a prominent contingent valuation study done by recognized experts in this approach, a study that should be only minimally affected by these concerns but in which the answers of respondents to the survey are implausible and inconsistent.

Now this is not a consensual view. Some academics still think that contingent valuation has promise, and others yet caution against too much optimism. My point, however, is that in the most controlled studies of public opinion and actual valuation, the results are at best "curious". This should make us very skeptical of direct democracy from the beginning.

So what is the evidence in favor of better outcomes from public consultations? Feld and Kirchgassner summarize the Swiss evidence. In cities with direct legislation, costs for garbage collection are lower, people are less annoyed about paying their taxes, people are more satisfied with their life as a whole, and their GDP perform around 5% better. Maybe that is all true. Switzerland is strange in several ways. It is one of the richest countries in the world despite being landlocked, mountainous, multi-ethnic, and squeezed between former imperial powers. Maybe the particularities of Switzerland's direct democracy scheme, which often relies on assemblies instead of simple ballot voting, help explain that. Or maybe we will find out in the future that the evidence is not as strong.

When Voigt makes a global assessment of the empirical effects of direct democracy, he finds evidence for greater government effectiveness and less corruption. These effects are only unambiguous, however, for mandatory referenda - i.e., consultations that are mandated by law, such as all constitutional amendments in Switzerland or some financial decisions. In the case of initiatives - where the public consultation derives from the desire of citizens themselves -, for example, their mere provision is associated with greater corruption at the 10% level, but each additional mandatory initiative reduces corruption by a bit.

Voigt stresses that " the effects of (mandatory) referenda are very different from the effects of initiatives. Whereas mandatory referenda are correlated with significantly lower overall government spending, initiatives are correlated with significantly higher government spending. We should thus be very careful when talking about direct democracy as different instruments are likely to cause very different outcomes." (emphasis is his). But this seems strange. If the main argument in favor of direct democracy is that it better elicits the will of the people, why should such a distinction produce such different results? Also, shouldn't we consider an initiative a much better expression of what direct democracy is? If the people only vote on the things their legislators want them to vote, are the objectives of direct democracy being accomplished?

When we talk about the risks of direct democracy, we see they are very large. There is a reason British Prime Minister Clement Attlee called referendums "a device for despots and dictators". As Nigel Jones writes,

Modern referendums can be partly blamed on, or credited to, the Bonapartes. France’s first referendum was held in July 1793 in the midst of the revolution, when all adult males were asked to ratify a constitution drafted by the Committee of Public Safety, the blood-stained executive arm of the National Convention. On paper the constitution, like that of Stalin’s Soviet Union, was impeccably progressive, even advocating the people’s right to rebel against tyranny. The problem was that it had been drawn up by Maximilien Robespierre and his cronies, no mean tyrants themselves.

[...]

When France’s menfolk next went to the polls, in 1800, it was Napoleon Bonaparte who demanded their approval of his destruction of the very Directory whose creation they had applauded six years before. The brilliant young general had returned home, after a string of military victories in Italy and Egypt, to make himself France’s dictator, or ‘first consul’, in a messy coup organised by his soon-to-be-disillusioned brother Lucien.

[...]

Like uncle, like nephew: Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, that strange amalgam of tyrant and democrat, reactionary and progressive, relied on referendums to give popular approval to his own violent seizure of power a generation after the first Napoleon had sailed into the sunset of St Helena.

[...]

Hitler only used referendums when he was sure what the result would be. It helped that techniques for manipulating and influencing public opinion had grown more sophisticated in the half century since Napoleon III’s rule. Under Joseph Goebbels’ control, German radio and cinema ensured that the Nazi regime’s message hit home. In August 1934 Hitler took advantage of the death of the aged President Hindenburg to call a referendum on merging the two posts of president and chancellor into one: the Führer.

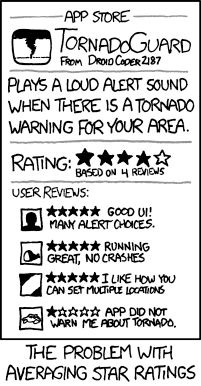

This means that even if direct democracy could potentially have some benefits - under very specific conditions - the risks are great. A xkcd comic helps illustrate this:

Direct democracy is worth exploring - very carefully - so that we understand exactly under what conditions it will bring benefits. But compared to parliaments, the results are much less clear-cut, beneficial, and safe.