Perils of Parliamentarism? Not so Fast

One study I missed in the empirical literature review of the effects of parliamentarism for political stability is Hiroi and Omori's "Perils of Parliamentarism." Giving its suggestive name and the fact that it goes contrary to my hypothesis, I regret not having included it. Let me correct for that here.

Before we turn to the specifics, I will say I'm not convinced of the paper's quality. If it was a high-quality paper, I would adjust my priors and decrease my confidence in the benefits of parliamentarism. But given that I find the paper's argument failing, I come out even more confident.

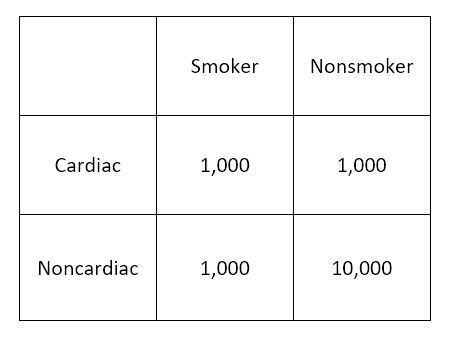

To see why, I will begin with an example. Suppose you are studying the effects of smoking on cardiac episodes. You divide your subjects in four groups: those that smoke and have had a cardiac episode, those that do not smoke and have had a cardiac episode, those that smoke and have not had a cardiac episode, and those that do not smoke and have not had a cardiac episode. The proportions are completely made up, but they are in the correct direction and will serve for our illustration:

We can see from the table that while 9% of nonsmokers have had a cardiac episode, 50% of smokers will have experienced one. This would be in line with the hypothesis that smoking is dangerous for the heart. But what if I'm like Ronald Fisher and am particularly skeptical of harms associated to smoking. I might say: "well, some people are already smokers and some people are already nonsmokers. Among those, some have experienced cardiac episodes. Should they change their behavior?"

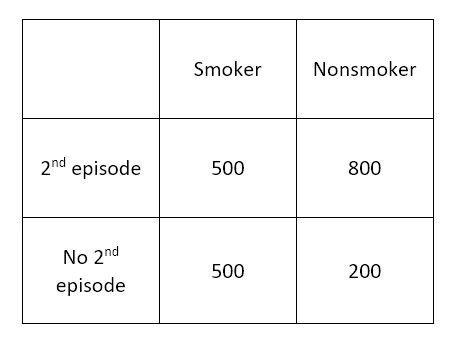

Now suppose that I investigated (and let me stress the suppose, I have no idea if this is true) and found out that, among the people who have experienced a cardiac episode, a second episode is more likely for nonsmokers than for smokers. Once again, I have no idea if this is true, but it could well be. People develop heart problems for many reasons, and these reasons which are not associated with smoking might make them more prone to experience a second episode.

Would you consider this as evidence that - even if their sole concern with smoking was their effect for their hearts - smokers should not quit? Surely not. The above evidence is perfectly consistent with smoking being always a risk for the heart and with quitting always helping. The reason the above analysis fails is that we are sampling on the dependent variable.

You will have guessed that this is exactly what Hiroi and Omori do in their study. They do not claim that parliamentarism countries are more prone to breakdown overall. They find that, among the countries that have experienced a breakdown, parliamentary countries are more prone to having another one, just like the smoking example. The abstract makes it clear that this is what is happening:

"Parliamentary systems are generally regarded as superior to presidential ones in democratic sustenance. This article contributes to the debate on the relationship between systems of government and the survival of democracy by bringing in a new perspective and analysing the experiences of 131 democracies during 1960–2006. We argue that systems of government do matter, but their effects are indirect; they exert their influence through societies' prior democratic records. Confirming the conventional argument, our data analysis shows that uninterrupted parliamentary democracies face significantly lower risks of a first breakdown than their presidential counterparts. Contrary to the common understanding, however, we find that the risk of a democratic breakdown can be higher for parliamentary regimes than for presidential regimes among the countries whose democracy has collapsed in the past. Furthermore, the risk of a previously failed democracy falling again grows as (the risk of) government crises increase(s). Hence our study questions the common belief that parliamentary systems are categorically more conducive to democratic stability than presidential ones."

Hiroi and Omori also commit a much more frequent mistake in this literature, which is to control for the annual level of GDP per capita and economic growth. GDP per capita and growth can't be considered independent by any measure. McManus and Ozkan (2019), Gerring (2009), and others find a positive effect of parliamentarism on GDP. This is frequently surprising but should not be, if we consider only three points: 1) in political science, there is close to a consensus that presidentialism significantly harms political stability and functioning, to the point that they make them more prone to breakdown, but in various other forms before that; 2) in economics, there is close to a consensus that institutions, "the rules of the game" as North puts it, are one of the most important factors in explaining economic growth; and 3) political stability and functioning and institutions as "the rules of the game" are deeply intertwined. If you accept the three propositions above, you should be surprised if forms of government did not impact economic growth.

For the reasons above, I come out a little bit more confident that parliamentarism has the positive effects I suggest. If it is rare that studies find a negative effect and we find some crucial issues with the studies that do find it, we should be more confident of the initial hypothesis.