Parliamentarism and legislator quality

One of the most common critiques I hear to proposing parliamentarism in a given country is that “it may well work for Europe where legislators are particularly public-oriented and honest, but not in my country.”

Most people who argue this way do not realize that this argument is of the type that claims that democracies work only if a population is sensible enough, and that some populations just aren’t. While I would not dismiss it just because it is not socially desirable to state such a thing, I will note that it does imply this socially undesirable conclusion. The soccer player Pelé once said that he did not think Brazilians were ready to vote for president. He was heavily criticized at the time and anyone one who suggests such a thing will be equally criticized. Why is it so acceptable to suggest, then, that Europeans and Canadians know how to vote for legislators but not Latin Americans?

Parliamentarists, instead, propose that voters in any given country vote – for practical purposes – equally well and equally badly. In a parliamentary environment, they vote well enough such that the incentives the legislators face will steer the country in a better direction, and they vote badly enough in a presidential environment such that the country’s outcomes will be far worse.

People are often skeptical that the incentive framework can affect in such a way behaviors which seem so intrinsically connected to the morality of the agents. But that is an error, which has its own fancy name: the fundamental attribution error. As Wikipedia explains, this is "'the tendency to believe that what people do reflects who they are',[1] that is, to overattribute their behaviors (what they do or say) to their personality and underattribute them to the situation or context."

Here is an example on how a simple rule can dramatically affect how fair and efficient a distribution of resources is. Suppose two kids have to split a slice of cake among themselves, and that the marginal benefit of more cake is decreasing - that is, kids prefer to have more cake than less, but going from no cake to a little bit of cake is much more valuable than going from almost all of the cake to literally all of the cake. It is clear then that the most efficient distribution is to split in half.

Kids may spend a lot of time arguing over who will be the decider on how to split. One may argue that he is fairer in general and the other more selfish. Then one may argue that they have a better sense of space and will do a better job dividing it evenly than the other. It may also be argued that one of them knows how to split in such a way that the cake's form is most intact. It is easy to see how all of these arguments may be met with distrust. If one of the kids is tasked with dividing the cake and assigning which portion goes to whom, we may expect that the divider may benefit themselves.

Now if the kids adopt the divide-and-choose method, they will easily get to the efficient solution. One kid is tasked with dividing the cake into two portions. The other will get to choose one of the portions for themselves, and the divider will get the remaining portion. The divider then has every incentive to be as fair as possible in the division, since he will get the portion which is perceived to be the worst by the chooser. Notice that if one of them genuinely is better in dividing cake without damaging the frosting, they will both agree this should be the divider.

Or think of what the equilibrium price is in a monopolistic market or a competitive one. Producers which follow the same profit-maximizing strategy will practice very different prices, making much more profit under a monopoly, and setting their production levels below the efficient level. This happens independently of any intrinsic altruistic motive in their part.

In this post, I will try to show through a simple numerical model, yet still realistic, that the choice over presidentialism or parliamentarism can have similar effects on the final behavior of an assembly.

Suppose 100 politicians have to decide on a project. They are all convinced that their own project is the best . They value that at 1000 (while the others value it at 0). The second best project has wider support, but is less valuable to each individual politician than their own personal project. Assume politicians each value approving the "common good project" at 100. Status quo is valued at 0.

Now suppose presidentialism.

The president wants to approve his personal project. He won’t get the votes, unless he uses transfers, which are taken from everyone proportionally. Now the president offers 10 dollars for the first 50 people who vote for his project, independently of his proposal passing or not. Given he controls allocation of resources because of his privileged legal position, he can do that kind of promise.

For any individual person, the choice is either vote for the status quo or vote for president’s proposal, because the president has all the agenda-setting power.

If they vote for the status quo, and it passes, they get 0 minus their share in the transfers the president made. Since the president's proposal did not pass, it will be less than 50, but not defined. Call that number X. Then they would get -X.

If they take the transfer and status quo passes, they get 0 (from status quo) + 10 (from the president) - X.

Better to take the transfer.

If they vote for the status quo and the president’s project passes, they will get -5.

If they take the transfer and the president’s project passes, they will get 5.

Bettter to take the transfer.

Taking the transfer is called a "dominant strategy" in game theoretic terms. No matter what others do, it is the best strategy from the politician standpoint. This means that, in equilibrium, the president's project will pass.

The transfers will cancel each other out, the net benefits will be the benefits for the president: 1,000.

Now suppose parliamentarism

All will have incentive to propose their own personal project, and promise transfers *if* project passes. Since they have no intrinsic executive power, that’s the only kind of promise they can make.

At least one person, however, may instead propose the common good project, and propose transfers to all the legislators who vote in favor.

Then the choices will be:

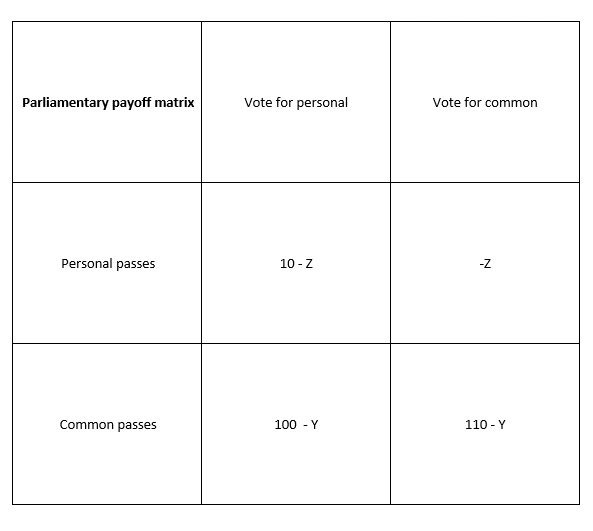

If they vote for the common project, and it passes, they get 100 (from common project) + 10 in transfers minus their share in financing the transfers, which depends on how many vote for the common project. Call this Y. Their benefit is 110 - Y.

If they vote for a personal project, and the common project passes, they get 100 - Y.

Better to vote for the common project.

Once again, transfers cancel out, and the total benefit will be 100*100 = 10,000.

If they vote for a personal project and that specific personal project passes, they get 10 (in transfers) - Z.

If they vote for the common project and a personal project passes, they get -Z.

Better vote for the specific project.

The total benefit, as in presidentialism, accrues to the proposer of the legislation, which is 1,000.

There is no dominant strategy at this stage. If the common project will win, better vote for it. If a specific legislator’s project will win, better vote for that. But, considering the incentive structure, all legislators will present their own project and offer transfers. The chance that any one legislator gets to pass their project declines, while the chance that the common project passes increases. The common project is a focal point. As the perceived probability that the common project will win increases, so does the expected value of voting for the common project. The common project becomes the expected outcome.

This model is extremely simple, but it allows us to see how changes in rules which do relate to the real differences between parliamentarism and presidentialism affect the outcome. A parliamentary model of decision-making allows for both greater total benefits, and more widely spread. Legislators appear much more selfish in the presidential system than in the parliamentary system, even though their preferences are exactly the same. These benefits should not be seem as so surprising - we are removing the monopoly on agenda-setting created for the president. The insight is not original, either. A related and much more elegant model which shows benefits to this type of political competition has been published by Brennan and Hamlin in their "A Revisionist View of the Separation of Powers".

Like all models, it leaves out a very large number of issues. One point is that this portrays a small direct democracy and not a representative democracy. The transfers are financed by resources coming from the legislators themselves, not the public. A second point is that we do not have the figure of parties, all people are voting by themselves. I believe the lack of parties is a feature of the model. First, it is widely accepted that parties are not as strongly organized in presidential systems, marked by the politics of personality. Second, parties also have to solve the problem of collective decision-making in very similar ways as countries. Indeed, some adopt more "parliamentary" forms while others more "presidential" forms. Assuming parties assumes away an important part of the problem.

A third point is that legislators are not exclusively self-oriented in any of the systems, nor are their preferences so homogenous. But the introduction of such altruistic characteristics, as well as variance among people, would make parliamentarism perform even better. Given that in the presidential equilibrium the benefits legislators get are disproportionately from participating in the presidential coalition and getting transfers (in this model, exclusively), one would expect more self-oriented people to be attracted to politics in that environment. In the parliamentary context, the common good projects prevail. More altruistic legislators would be attracted to participate in politics.

In any case, pointing out that details have been left out is not enough to properly criticize a model. One needs to show how the introduction of these details would change the conclusion. I don't see how it would.